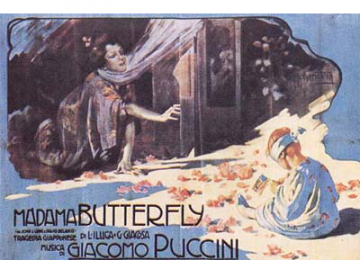

I was first introduced to Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly (1904) in my undergraduate history survey course. My professor (Kirsten Yri, Wilfrid Laurier University) encouraged us students to view this work with an especially critical eye, pointing out the inherent cultural appropriation and Asian eroticism embedded in the opera and its libretto. Indeed, misogyny, xenophobia, sexual exploitation, and suicide are all prevalent themes in Madama Butterfly. As I continued my studies at Laurier, I had lengthy discussions with Prof. Yri about whether she should continue to teach Madama Butterfly, and if the opera should remain on 21st-century syllabi. These questions permeated the walls of the classroom as well, with many opera companies engaging in similar debates: Can the opera be staged effectively? Should the opera be staged at all? Does this work need to be wiped from the canon?

These are difficult questions that no one opinion can answer wholly and effectively. Different opera companies have turned to re-examining the work through community endeavours and equitable approaches to stagings, often focused on anti-Asian racism. There have also been contemporary artistic responses to the opera, such as interdisciplinary composer/performer Teiya Kasahara’s 笠原貞野 reimagined electronic music work that reclaims the original intentions of the Japanese melodies Puccini misused.

Some of the above questions were explored in my first graduate seminar course at the University of Toronto, taught by Prof. Ellen Lockhart entitled “Geographies of Opera: Wagner and Puccini.” After spending a week considering the misappropriation of Japanese music in Madama Butterfly, I once again sought to understand the origins of this work and further explore the storied history of Chô-Chô-San herself (also known as ‘Butterfly,’ the opera’s main character).

In pursuing this direction for my final project, I compared the two most cited sources for the opera’s libretto: Pierre Loti’s 1887 novel Madame Chrysanthème and John Luther-Long’s 1898 short story “Madame Butterfly.” Loti’s work is semi-autobiographical, detailing the author’s temporary marriage to a Japanese woman during his station in Nagasaki (a Japanese port city). Luther-Long was American, and he accredited his work to his sister Jennie Correll’s eyewitness account of her Nagasaki neighbour’s temporary marriage to an American sailor, that she saw during her stay in Japan as a Methodist missionary. These two accounts each have a similar narrative response, or re-interpretation.

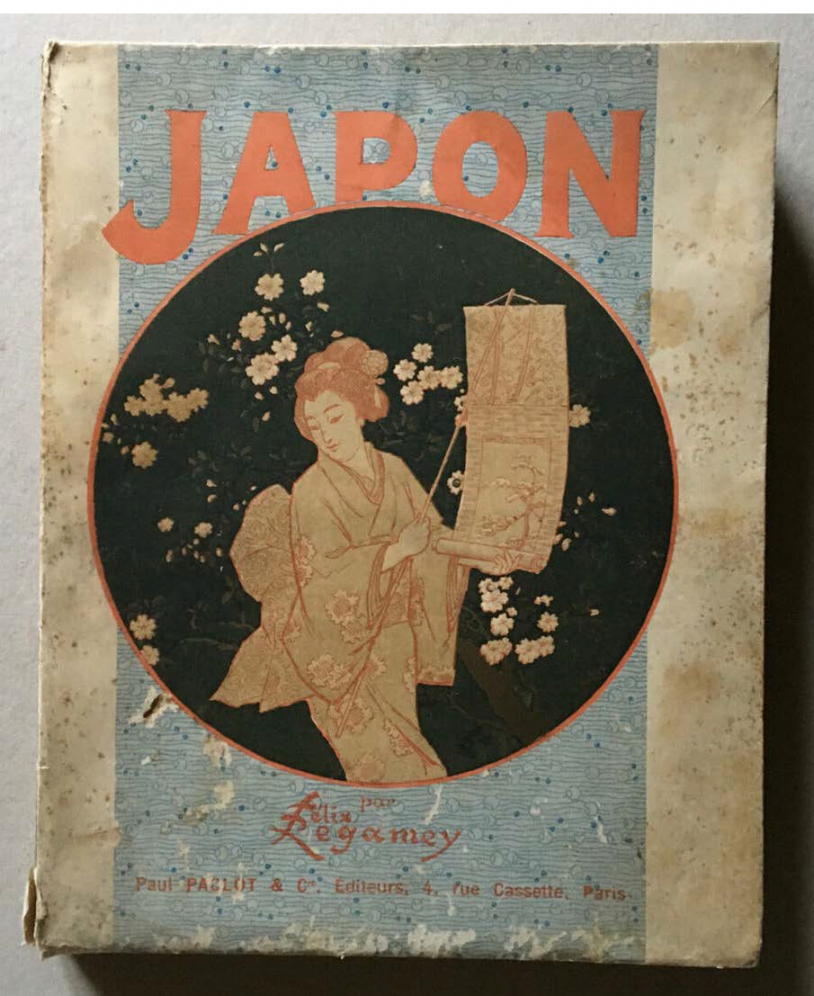

As Loti’s novel grew in popularity, artist and writer Félix Régamey was inspired to write his short story Le Cahier Rose de Madame Chrysanthème in 1894. Régamey was an original creator of the Japonisme art style in France. It is thought that the illustrations in Loti’s novel (by Luigi Rossi and Félician Myrbach) began to gain more circulation than Régamey’s own Japan-inspired art, causing him to respond by creating a work that he felt remedied Loti’s self-indulgent and cruel portrayal of Japan. Régamey shifted the perspective from Loti to Chrysanthème and gave the titular character a backstory. He also introduced Chô-Chô-San’s suicide, a plot point usually accredited to Luther-Long.

In America, playwright David Belasco rewrote Luther-Long’s work for the stage, premiering the one act play Madame Butterfly: A Tragedy of Japan in 1900. Puccini himself attended this premiere, essentially marking the genesis of his opera. My research explored potential connections between the French and American works, showing how remnants of each story can be found in the materials, story, and music of Puccini’s opera.

Still, at the core of these Euro-American stories are Japanese women. Who, fictionalized or not, represent the countless women subject to temporary marriages during the Meiji Restoration. In my effort to uncover Chô-Chô-San’s personal history, I found that Puccini’s portrayal of her is not a one-time tale of the unfortunate ending to a Japanese woman’s marriage, but rather a universal symbol of numerous women’s lost stories as a result of the domestic abuse, colonialist beliefs, and misogyny of Western sailors docked in coastal Japanese towns. My paper draws connections between each text and Puccini’s opera, with the purpose of uncovering the fault lines within Western iterations of a Japanese woman’s story, rather than drawing an impenetrable line between the opera and one specific source of inspiration.

Throughout researching the nuances of these four texts and their manifestations in Puccini’s opera, Prof. Lockhart showed me the Ricordi online digital archive, which contains a plethora of photos and letters associated with the original productions of Madama Butterfly and other operas. Using some of these materials to show narrative coherences helped paint a more accurate picture of Chô-Chô-San. This opportunity was particularly enlightening and helped me as an opera viewer better analyse a work I had struggled to criticize and understand for years. In making my poster, I had the opportunity to display some of these materials in conjunction with my writing for my teachers and colleagues (see pictures below). This opportunity genuinely excited me as there is such a lack of visual media used in traditional scholarship.

My work has not solved the debates or struggles of staging Madama Butterfly in the 21st-century, but it has allowed me to gain a much fuller picture of this work’s narrative and cultural history. This new understanding invites reflection on the opera’s origins and its broader cultural significance, affirming its place as a poignant exploration of cross-cultural encounters. It must also be remembered that none of these texts will ever tell the whole story. With the Butterfly narrative taken from Japanese women, the story will forever remain engrained and rooted in the colonial powers that provoked the abuse of Japanese women for temporary marriages in the first place. With such a lack of paper documentation about the number of women victimised into falsified love and eventual abandonment, this opera can be viewed as a placeholder for all those that were forgotten, highlighting the importance of cultural preservation and critical analyses of colonial narratives.

Kristen Whittle is an MA student in musicology. Kristen’s current research interests include intersections between music and literature in the nineteenth century, as well as domestic music and its representations in fiction and the press. Her studies are supported by a Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master’s Award from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Kristen holds a Bachelor of Music in history and theory from Wilfrid Laurier University (2023) where her undergraduate thesis (supervised by Dr. Kirsten Yri) considered emergent romanticism and music in Jane Austen’s novels. In her free time, Kristen enjoys reading, and spending time with her cat, Felix.

Kristen Whittle is an MA student in musicology. Kristen’s current research interests include intersections between music and literature in the nineteenth century, as well as domestic music and its representations in fiction and the press. Her studies are supported by a Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master’s Award from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Kristen holds a Bachelor of Music in history and theory from Wilfrid Laurier University (2023) where her undergraduate thesis (supervised by Dr. Kirsten Yri) considered emergent romanticism and music in Jane Austen’s novels. In her free time, Kristen enjoys reading, and spending time with her cat, Felix.