When one enters the Music Library as a conducting student, it is easy to be tempted by the striking presence of "the score." Mistakenly, the score is often the first and only stop of the conductor with a busy schedule, a number of rehearsals to lead, and a very short amount of time to learn an orchestra or a choir’s repertoire as if they wrote it themselves. Ultimately, we act as a vehicle for curiosity and excitement, and receive our energy from our studies, our own passions, and most importantly, from the energy and commitment of the musicians we work with, whose dedication makes said music-making possible. It is the conductor’s responsibility to enter these rehearsals with a commitment to the project at hand, a sincerity demonstrated in our approach, and the clear communication of our appreciation for the musicians involved. This is always noticeable in our level of preparedness. One of the long-standing questions for a conductor still stands: what is the best way to prepare? Is there a correct way? What are the crucial elements of score study for a conductor who wants to feel a true sense of connection to the score?

My relationship with score study has developed tremendously in the past year. Due to the sheer number of rehearsals and seminars—where one minute, one must have Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier Suite or Puccini’s Intermezzo from Manon Lescaut in their hands, and in the next, the works of Handel, Glick, and more prepared for an evening choral rehearsal—I have had to learn to expedite my score study while still striving to gain a very rich sense of the musicianship necessary to conduct it. Ultimately, I wanted to figure out a way to complete one sole task: do the score justice. The materials I have borrowed from the Music Library (my personal "borrowed collection") has shifted to support this new process of score study.

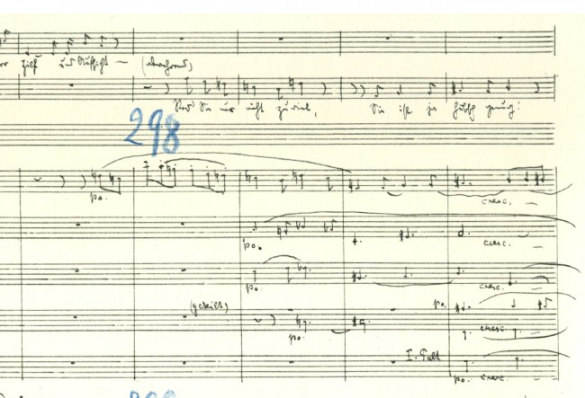

So, what is this new process? One ambition I had throughout the year was to support my expedited studies via a rich and well-researched understanding of performance practice and stylistic conventions. When I look at scores, I can find similarities in this capacity, and I am also able to draw upon historical context to gain a greater understanding of the musical elements that I need to bring out during a performance. In particular, I find that this understanding of historical context promotes a keen awareness of nuance—as we know, nuance is paramount in sensitive music-making. My current borrowed collection aims to support and inspire this sincerity, including texts that range from the score itself, to piano reductions (so I can connect with the music on my own instrument), piano four hands reductions, musicological and theoretical texts on themes found in the music, composer biographies, histories of the era in which I am working, and a plethora of others. However, there is one crucial text necessary if one is to seek out true nuance that they cannot always find in the score, in an analysis of the music, or even a book about the time in which it was written. If one wants to gain a greater understanding of the life of a composer, one ought to turn to their letters.

The seeming neglect of this most precious music-making tool in our music library will not limit the scope of a conductor’s imagination, but will certainly enhance it. If you are a romantic like I am, then at the very least, you will find that reading the words of certain composers will prove to be an utterly crucial element when preparing to play their music with extreme sensitivity and awareness. I wish to make it very clear that musical sensitivity exists in many fashions, and this is but one kind: to be motivated by a letter is merely one means by which your curiosity may be sparked, and is certainly not the only way to draw inspiration. Perhaps you feel most enthused by comparing works of composers and searching for notable differences, or perhaps you use analysis to inform your interpretive choices; regardless, you should employ methods that inspire and motivate you as you prepare works for your respective instruments. I must confess to an initial concern for reading the private words of another. I concluded, however, that my intentions were what counted; as they were good and truly curious in the best of ways, I decided to employ these letters as a foundational element in my score study process.

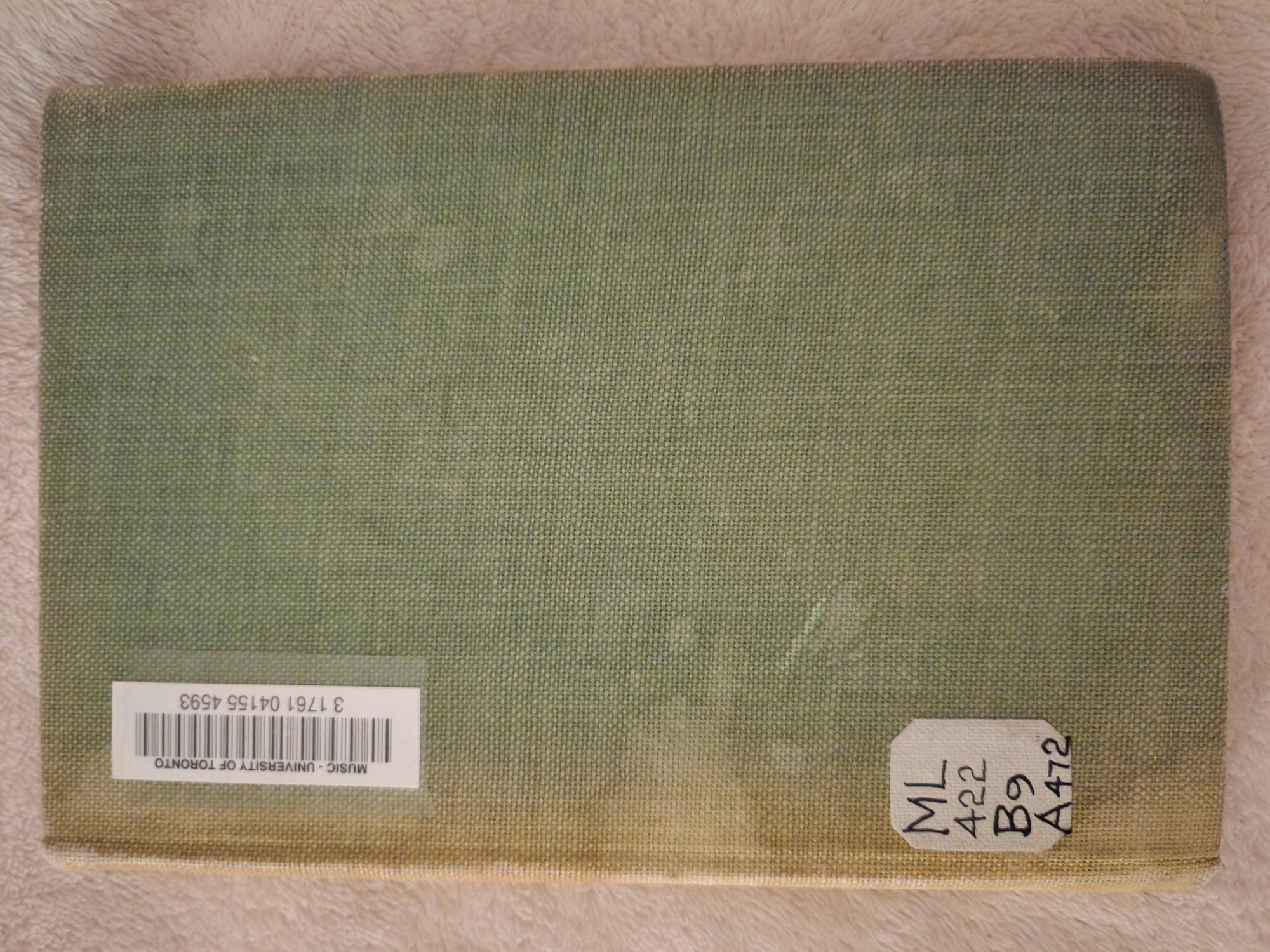

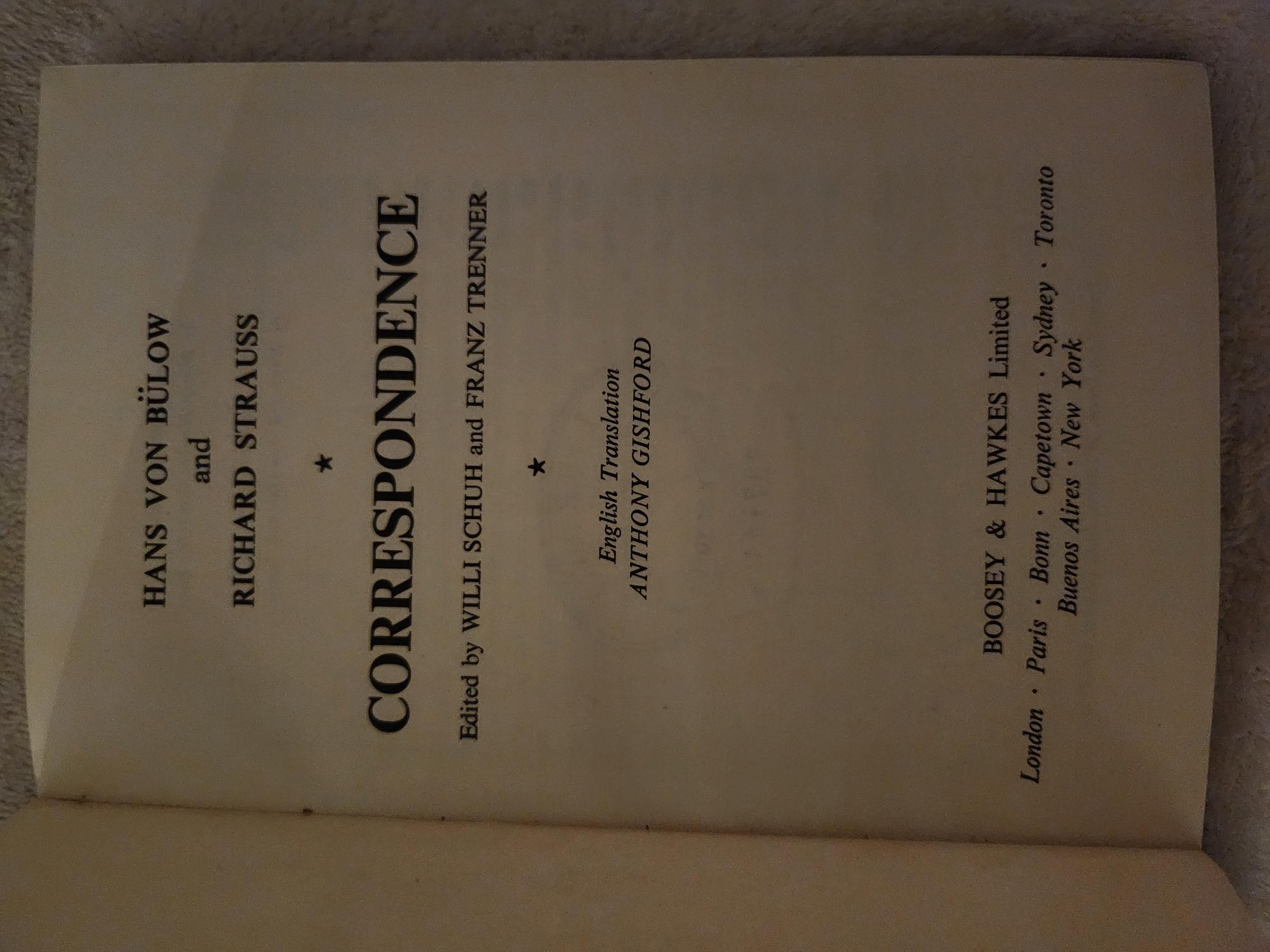

Which letters were most fascinating? Well, in particular, I came across a book that looked as though it had been neglected for quite some time … poor Mr. Book! I pulled a small green text from the library shelves: ML422 .B9 A472. Lo and behold, I opened the cover to find that it was a collection of letters sent between a young Richard Strauss and one of the most revered conductors of the 19th century, Hans von Bülow. From this text, I was able to gather a multitude of new ideas about the works of Strauss and the tendencies of von Bülow, culminating in a rich connection with the scores I was working with back in the Fall of 2022. Details were revealed not only about specific premieres, but also about institutions such as Bayreuth; it is an incredible primary source reference.

Perhaps most intriguingly, I learned that a young Strauss was wildly confident and did not hesitate to send a number of letters to von Bülow asking whether he might have works premiered, to share of his conducting ventures, and more. Notably, in all of this, he still gives off an air of incredible respect and courtesy, despite his excitement and enthusiasm with regards to their correspondence. Beyond this, it was fascinating to trace the development of their relationship via these letters. From a young Strauss sending multiple letters in a row with no reply (yet with an immortal enthusiasm), to formal conversations, to more intimate discussions of personal matters like illness or strife, it was truly an honor to read these letters and to be in the presence of these two musicians.

Now when I sit with Strauss’ works, I spend just as much time reviewing these letters, searching for nuance and development. I search for formal devices particular to that score and hypothesize reasonings for it in the letters in this book. I hear allusions to the works of other composers much more imaginatively. I reflect upon the personal concerns that I read carefully and mindfully. While it is important to consider that drawing conclusions about a work with only one reference or without a direct linkage between a primary source and a score often needs further review, it is a wonderful place to start seeking inspiration and broadening the scope of one’s imagination both as a performer and as a researcher. I look forward to building my borrowed collection even more so in the coming year, but I am also certain that the Music Library would appreciate it if I returned said captured collection at some point! Thus, when I have completed this necessary task, I then cannot wait to continue exploring the treasure trove that is the University of Toronto Music Library.

Emma Colette Moss is a Czech-Canadian conductor, researcher, and pianist with a passionate commitment to enhancing the accessibility of music for all audiences. She is currently studying at the University of Toronto, pursuing a Master’s in Music in Orchestral Conducting under the guidance of Uri Mayer. She completed her Undergraduate Degree with Honours in Composition and Piano Performance at the University of Toronto, where she received awards such as the Monika Ryckman and Ben McPeek Scholarships, along with a faculty-supported Rhodes Scholarship nomination. Additionally, she maintains her ARCT credentials in all Theory subjects and Piano Performance. She has studied under artists such as Larysa Kuzmenko, Jamie Hillman, Alexander Rapoport, Ivars Taurins, Melanie Paul Tanovich, Matthew Emery, Elaine Choi, Tracy Wong and Tanya Gernburd. With opportunities such as co-directing and co-founding the Sinfonietta Aionia, collaborations with the Greenroom Collective, Orchestra Breva, Concreamus Choir, Babel Chorus, and Mississauga & Oakville Symphony Orchestras, Navona Records, Emma Colette Moss has shown herself to be an emerging and passionate artist of note, developing her abilities for well over 15 years. Currently, she is Assistant Conductor of Pax Christi Chorale, works with Toronto Children’s Chorus, and holds a conducting position with the University of Toronto Symphony Orchestra. Her studies supported by a 2023 SSHRC CGS-M award, she is an active interdisciplinary researcher at the University of Toronto under the guidance of seminar supervisors such as Ryan McClelland, Steven Vande Moortele, and Sean Wang; her main interests include contemporary Grieg scholarship and hypermetrical analysis of First Viennese Works.

Emma Colette Moss is a Czech-Canadian conductor, researcher, and pianist with a passionate commitment to enhancing the accessibility of music for all audiences. She is currently studying at the University of Toronto, pursuing a Master’s in Music in Orchestral Conducting under the guidance of Uri Mayer. She completed her Undergraduate Degree with Honours in Composition and Piano Performance at the University of Toronto, where she received awards such as the Monika Ryckman and Ben McPeek Scholarships, along with a faculty-supported Rhodes Scholarship nomination. Additionally, she maintains her ARCT credentials in all Theory subjects and Piano Performance. She has studied under artists such as Larysa Kuzmenko, Jamie Hillman, Alexander Rapoport, Ivars Taurins, Melanie Paul Tanovich, Matthew Emery, Elaine Choi, Tracy Wong and Tanya Gernburd. With opportunities such as co-directing and co-founding the Sinfonietta Aionia, collaborations with the Greenroom Collective, Orchestra Breva, Concreamus Choir, Babel Chorus, and Mississauga & Oakville Symphony Orchestras, Navona Records, Emma Colette Moss has shown herself to be an emerging and passionate artist of note, developing her abilities for well over 15 years. Currently, she is Assistant Conductor of Pax Christi Chorale, works with Toronto Children’s Chorus, and holds a conducting position with the University of Toronto Symphony Orchestra. Her studies supported by a 2023 SSHRC CGS-M award, she is an active interdisciplinary researcher at the University of Toronto under the guidance of seminar supervisors such as Ryan McClelland, Steven Vande Moortele, and Sean Wang; her main interests include contemporary Grieg scholarship and hypermetrical analysis of First Viennese Works.