The following is a guest blog post contributed by Eric Yang, a fourth-year student at the University of Toronto Faculty of Music, featuring archival research completed at the University of Toronto Archives and Music Library. Read more in part one, which covers the construction of the Edward Johnson Building.

In September 1962, students finally walked into the new building. The following post will detail the design of the Edward Johnson Building at the time of its construction. Sources are taken from a speech given by the architect (Adamson) in January of 1961, a speech by Neel given (quite ecstatically) during a tour in Regina, and the architectural floor plans made during construction.1

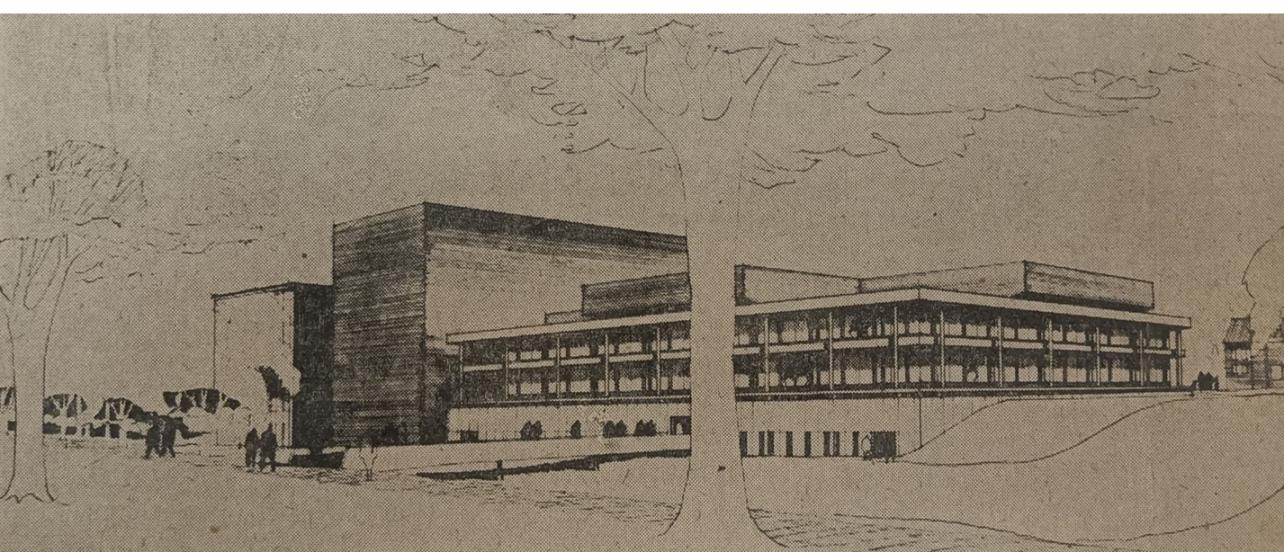

The Edward Johnson Building was planned and built around two main performing spaces : the recital (Walter) hall, and the opera (MacMillan) theater. The lot itself created an issue for the design. Since the site of the building slopes into Philosopher’s Walk, three-and-a-half stories of the building show on the East side, while four-and-a-half stories show on the West, where a bridge connects the building’s upper basement level to Philosopher’s Walk. Image 1 shows the original bridge design with concrete railings.

The Edward Johnson Building contains five (and a half) floors. The first and second floors are wrapped around the MacMillan Theater to protect it from external noises and to reduce the visual complexity of the building as seen from the outside. The classrooms, offices, and studios on the first and second floors all contain large windows to allow for views of the ‘handsome’ Philosopher’s Walk. The windows are set back from the face of the building to provide shade and to give definition to the façade of the building. The first floor and main foyer contained offices, classrooms, and a coat room that could hold 1000 coats. It has since been demolished for the library extension. Washrooms were placed on the first floor and lower basement floors to avoid crowding between the two concert halls.

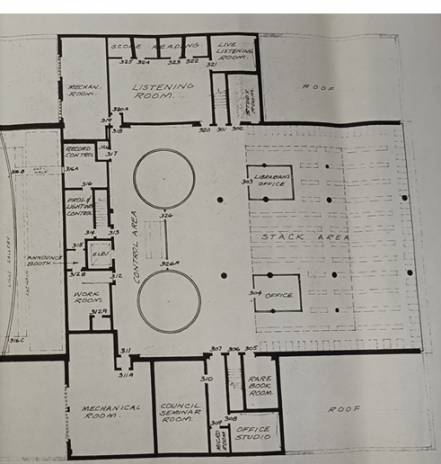

The third floor contained the library, along with offices, a darkroom, a listening room, and a rare book room. Sunlight streams from two circular shaped windows carved into the ceiling, that streams down into the first-floor foyer. This feature of the building must have been seen as quite impressive, since it made it into both the opening ceremonies program and the brochure for the Johnson Memorial Library. The current office for the Undergraduate Association used to be the darkroom (workroom on floor plan) and the current instrument storage room used to be the rare book room. The listening room was turned into the keyboard harmony room, and the listening booths are now unused. The announcement booth has been turned into a storage room, which the author finds rather odd, since it seems that it would still serve a function for the theater. Adamson says that he was forced to not place the same large windows on the third floor since it would unbalance the building due to the ‘forceful brick structure’ that was the opera theater.

Since the building was designed around the two performing stages, the lower basement foyer and the main floor foyer were built to accommodate large amounts of people that might spill out after a performance. The main entrance and Philosopher’s Walk entrance were also designed in this way; thus, each performance hall could be served by a separate entrance and foyer to avoid crowding.

The opera (MacMillan) theater seats 860 people. The stairways on its left and right lead up to the balcony from the same foyer. Double-layered walls were used for the opera theater to avoid sound spillover, as were the double doors from the foyer and into the upper basement. The wood walls and back wall of the opera theater were designed for acoustic considerations, as is the plaster ceiling which has breaks to allow for lighting. The orchestra pit was designed after studying the Wagner Bayreuth theater at great length; it accommodates 85 musicians. The pit is operated by a mechanical platform, although this was not finished until after the opening of the theater. The stage of the opera theater is the same size as the O’Keefe Centre, which at the time of construction meant that MacMillan Theater was the largest opera house in Toronto. Backstage a freight elevator serves multiple uses. It connects backstage to the workshop in the lower basement, to the loading dock behind the theater, to the practice rooms in the basement, and with the second floor. The idea was that the one elevator could move pianos up to the second floor (a gallery over the stage bridged the gap made by the theater) and the practice rooms and move sets from the workshop to the stage.

The lower floors contain wardrobe rooms, make-up rooms, and dressing rooms with washrooms, along with offices for a director, stage manager, and opera staff. The rehearsal stage (Geiger Torel Room) and instrument rehearsal room (Boyd Neel Room) are both equipped to house 200 musicians. They are both acoustically treated for either voices (rehearsal stage) or instruments (instrument rehearsal). A control room connects the two rehearsal rooms. Interesting to note is that the CBC, during the construction of the Edward Johnson Building, installed their own native broadcasting equipment into the control rooms, allowing for live broadcasts from either room. The author hopes that this capability was used before becoming obsolete. On the lowest floor, there are 25 practice rooms along with the electronics department. Where the harp rooms are now used to house two organ practice rooms; the fate of those organs are unknown, since there is only one organ practice room now.

The recital (Walter) hall seats 500 people. At the time of completion, the organ was not yet built, and a fundraising campaign was started to raise money for the Walter Hall organ. Adamson says, “the projection booth in the back and the sound reflector over the podium will make it an unusual and interesting room.” The organ was built by the end of the 60s.

The design of the exterior of the building was given a lot of thought in the original speech. The reddish-brown brick was chosen to harmonize with the law building and with the Royal Ontario Museum. They are also laid in a special pattern with a spectrum of browns to elevate an otherwise dull wall. Care was taken to preserve the trees that surrounded the lot, a difficult task as explained by the architect, but it saved the large trees that currently grow along the path of the old Taddle Creek. The columns along the outside are finished in a rough stone, which also harmonizes with the surrounding nature.

The most important and more difficult part of the entire construction was sound. As the school functions with multiple areas of sound creation, unwanted sound and unamplified sound were major concerns for the architect. Starting with the practice rooms, the idea was to find a happy medium in terms of sound, to both shield the practice room from unwanted sound from the neighbouring rooms, but also for the student to be able to hear their own mistakes. Thus, the practice rooms make use of floating floors, separate walls, and a sloping hung ceiling—each room is a complete box, structurally separated from the rest of the building and from the surrounding rooms. The walls are made from sound absorbing materials so that the student can both hear themselves practice but not disturb others, while also absorbing echoes for a dry environment. Another major concern was heating and cooling. Air ducts would transmit sound from one room to the next! To fix this, hexagonal dividers were installed throughout all air ducts, providing a barrier for sound waves, while still allowing air to travel through them. Furthermore, the heating and cooling system is housed in Varsity Arena and is piped under Philosopher’s Walk. This is to avoid the extra noise and vibration that might disturb performances. Image 4 below shows one more quirk of the building, which is that those vertical bricks in the main foyer and lower basement foyer are air ducts, to provide constantly flowing fresh air moving through the foyers.

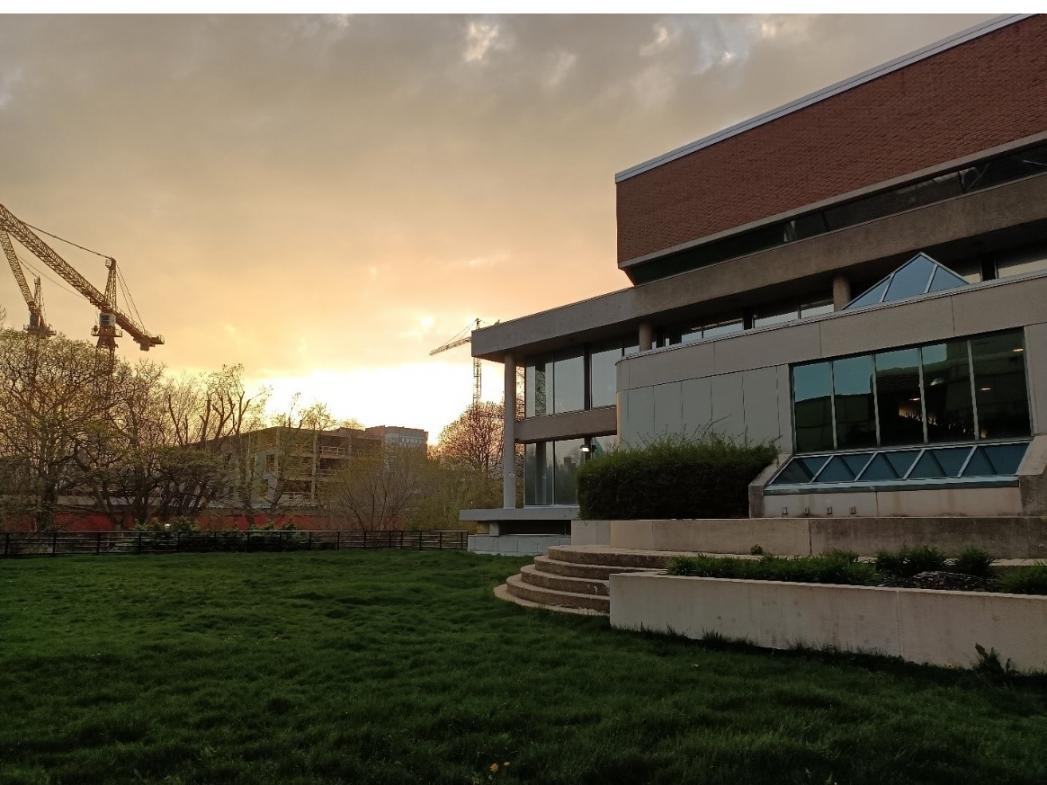

The Edward Johnson Building is officially in its 60th year. Between 1964 to 2024, an extension, including the current library was built (the Rupert E. Edwards Wing, groundbreaking ceremony on July 14, 1988); the student commons were moved from room 130 to the third floor; some asbestos from the construction was removed; accessibility was improved; 90 Wellesley was added for more space; the old McMaster Hall that housed the School of Music was renovated and extended; the seminar room on the third floor was replaced with a rehearsal room; and a café (which was the only feature that the School on College Street had that EJB did not) was built.2

Dean Neel’s original 1954 argument for a new building calling for more student space considering growing enrollment becomes more and more relevant as we grow more and more disillusioned with the ever-aging Edward Johnson Building. More room for classes. More offices. More performance spaces. I have only heard of all the headaches that this building has caused, all the issues and problems when it fails to reach expectations. It is sometimes nice to look back on when this was all a far-fetched dream, and a building to be so proud of when it first opened: the first purpose-built music school in Canada.

Notes

1. University of Toronto Archives, University of Toronto. Faculty of Music, Gordon Adamson speech (1961); Boyd Neel speech (1962); Floor plans (6 maps) (1962), A1975-0015/003. [return]

2. Richards, Campus Guide, no. 80. [return]

Acknowledgements

A great deal of debt is owed to Becky Shaw at the Music Library Archives, for finding so much information about the construction of the EJB, and for her expertise in organizing and picking out only the most useful of tidbits and images. Furthermore, thanks are owed to Andrea McCutcheon at the Robarts Archives, for sifting through boxes of restricted Faculty of Music files—just to single out the ones on the construction of the EJB.

Bibliography

Published Volumes

Richards, Larry Wayne. University of Toronto: The campus guide: An architectural tour. Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009.

Schabas, Ezra. There’s Music in These Walls: A History of the Royal Conservatory of Music. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2005.

Archival Materials

University of Toronto Music Library. John Beckwith fonds. OTUFM 10.

University of Toronto Music Library. Faculty of Music collection. OTUFM 04.

University of Toronto Archives. Faculty of Music collection. UTA 0106.

University of Toronto Music Library. University of Toronto Opera Division fonds. OTUFM 84.

University of Toronto Archives. University of Toronto President’s Reports.

University of Toronto Archives. Eric Trussler Photographer fonds.